| English library about Russian climbs:

DENIS URUBKO (ALMATY) About Baruntse - Annapurna expedition (Spring 2004)

Fascinated by our chance to answer the calling of this 1750m high face, we returned to Nepal in the spring of 2004. The author of the idea and the leader of the expedition, Italian Simone Moro, is one of the leading professional alpinists of the world. Reflecting our sport ambitions, the group selection was extremely limited. Simone chose Bruno Tassi, a mountain guide and rock climber, and myself, representing the Central Army Sport Club of Kazakhstan and bonded with Simone by many years of friendship and our common experience from Himalayan expeditions. From

Kathmandu, the route to the mountains begins with a trek in a caravan

of Sherpas or pack yaks. Lukla, where you normally get by a plane,

marks the start of the trek, from a deep canyon to snow-covered

peaks. Not one of the numerous tourist groups we met along the way

believed that we with our modest luggage are in fact a mountain

expedition. However, news of our venture, as it was called, somehow

moved through the air and we were met everywhere with much respect.

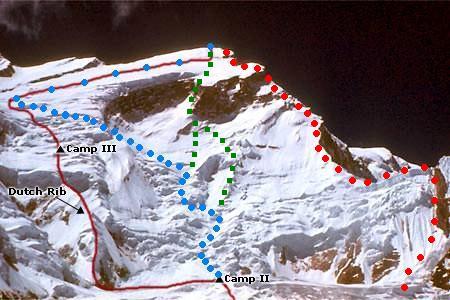

It was time to deliver. After some reconnaissance and short but wild discussions, Simone, Bruno and I decided on the safest variant. At the top end of the wall, two icefalls were baring their white teeth. One has to be very cautious in a Himalayan first attempt, which is why we chose a buttress in the left side of the northwest wall Kali-Himal for our route. Moro and Tassi took on the start of the route, through steep ice and rock walls to a plateau around the icefall. Afterwards, Korshunov and I exchanged them. Our task was to acclimatize for higher elevations and get a feel for the character of the route – its tough and easy spots, type of the rock, possibility of bivouacs on the wall. Bruno

elegantly climbed the rock part of the rib. At approximately 6200m

Boris and I rest in a wide band of overhanging rock. The weather

worsened in the mid-April and, climbing in streams of snow and whirls

of storms on slabs and cornices, I had to draw on all my years of

experience. Fortunately, our work was slowly coming to an end. We

succeeded in climbing about 100m per day and named this section

the “traverse of the suiciders”. Our

clothing helped us a lot. It used to be that you had to adjust this

and watch that all the time but now you just zipped up in the morning

and that was it – BASK worked. The

weeklong period of snow soon changed for freezing cold hurricane

winds at an elevation of 6,500m. Even the sun, hanging in an ultramarine

sea, was freezing in this cold. On

April 30, we stormed the mountain. We were receiving bad weather

forecasts and warnings from everywhere. “Don’t go!”, everyone was

saying, “It is time to wait!” Nevertheless, Simone and I, feeling

lucky, managed to convince Bruno to join us. The two days of work in the ledge belt were well worth the effort. Here, after the same overhang I went over last time, somewhat easier rock appeared. But the cold and wind were a strong mix and we had to climb in gloves, front-pointing on our crampons. Drytooling on CAMP’s Awax icetools, scratching under snow and ice in search for the microscopic features to hold yourself on. But the pleasures, as you may well know, do not last long. On top of all this, hammering pitons in an uncomfortable position, I smacked flat my pinky finger. Nevertheless, hanging in the portaledge in the evening, I felt content about our today’s work. The road ahead laid now open. The next day, balancing around with our heavy packs, we continued along rock and ice slabs towards the sub-peak ridge. We again worked in hurricane winds, and hammering in the ice-crews it struck me how deeply frozen the high-altitude Himalayan ice is. Its dark blue color was almost haunting. Building our portaledge camp on the snow ridge at 6700m in the twilight of the day is better forgotten. The morning greeted us with a thundering roar. On the east of us stood the massif of Makalu, and it was clear that the winds reigned there as well. In this final day of the assault our route followed a steep snowy ridge – as if a springboard to the sky. At 11a.m., on the summit, Simone, Bruno and myself watched all the highest peaks of the planet bow under the gusts of wind. Or was that a tribute to our persistence? Or just a vision? We

reached the base came the following evening after a twenty pitch

rappel. The air was still at the base of Kali-Himal. With a happy

grin, cook Tsering made us a dinner of pizza, spaghetti, and tea

with compote. I noticed the myriads of stars twinkling in the sky

as I was sipping from my mug. It was cozy and still at the camp,

yet somewhere out there, unseen, icy wind was whirling, a messenger

of the Tibetan mountains. So good, I thought, that him and I did

not cross our ways! * * *

Annapurna (8091m) was the first 8000-meter peak summited by people. Not that this means much; many expeditions attempted to summit other 8000-meter peaks time and again: Everest, K2, Nanga Parbat. Annapurna gave in at the first try. A true drama unfolded on its slopes in 1950, and the French alpinists Herzog and XYZ (the transcript of the Rusified name is clearly wrong - Lachenal) miraculously managed to return from their successful summit bid. These days, Annapurna is the 8000-meter peak summited by the fewest number of people. Kazakhstan climbers never succeeded in climbing the mountain. In 1988, Valiev and Moiseev planned to do so but for some reason changed their plans later on. Instead, together with a Slovak mountaineer Zoltan Demian, they set a beautiful new route on Dhaulagiri that fall. A new climbing pair appeared at the base of Annapurna in the winter of 1997: A. Boukreev and D. Sobolev. Simone was with them. They begun their ascent of the mountain along the south-west ridge but bad weather covered the whole route with heavy snow. On December 25, an avalanche from Fang peak buried the Kazakhstan’s alpinists. Simone survived by a chance, yet suffered serious injuries. Annapurna

is a beautiful mountain. Its beauty is full of charm that cannot

be described in logical terms. It is simply magnificent, as if to

challenge human ambition. It is obviously not by a chance that its

name is the second name of the Hindu goddess of fertility Lakshmi.

This goddess personifies the primary living energy Shakti that gives

existence to everything in the world. Hindus treat her with flowers,

sweets, rice and saffron. In the spring of 2004, Simone and I decided that the time has come for another adventure. The mountain was still equally dangerous, but our experience of climbs of the 8000-meter peaks in the course of the past few years added to our confidence. That is why we decided to “do” a new route along the north rib of the mountain – our little but beautiful note in the melody of the Himalayan mountaineering. The first ascents always bring something new to sport mountaineering. They are about understanding the nature and yourself. The will to make the step to the unknown, to risk setting a route that has never been done before – all that is of interest to the world of mountaineering. Typically, a new route is created because all the other simpler routes have been done before. And the fact that the alpinist prefers a route not climbed by anyone to a more reliable route on the mountain set by other people gives reason to judge the person as someone willing to risk the success for the sake of self-expression and discovery. In alpinism, this also characterizes you as a sportsman. After the expedition to Kali-Himal, Bruno went home while Simone, Korshunov and I appeared under Annapurna on May 15. The funding for the expedition came from Simone, Rinat Khaibullin and the American Anatoly Boukreev Foundation. The management of the foundation was able to find sources to support our attempt, as it always tries to support Kazakhstan alpinists. There were three more alpinists with us at the base camp at 4100 meters. Leader of the expedition R. Diumovich from Germany, an Austrian climber G. Kaltenbrunner and Hirotaka from Japan tried to summit Shishapangma in April and now intended to summit Annapurna. It was difficult to find a more international group in the Himalayas this spring. We were all from different countries with the exceptions of Ralph and Gerlinda was Germany and Boris Stepanovich and me being Russian. We

started the ascent a few days later. The four started first, and

Simone and me headed up two days later with all our heavy gear.

The idea was that Ralph, Gerlinda, Hirotaki and Boris Stepanovich

Korshunov) would climb Annapurna together along the standard first-ascend

route. Simone and I wanted to test our mettle on a rocky buttress

on the right side of the standard route. The buttress starts at

around 7000m and rises sharply to 7300m. The steep ice walls above

and below the buttress make the route more difficult. Things were getting on less brilliantly for the two of us. The climb with heavy packs in deep snow was very tiring. Moreover, Simone felt sick and could hardly cope with the last few meters. Rested after the supper, we agreed that climbing the new route is not realistic for us at the moment. My grief knew no end. The goal was rising right above us – cherished yet exhausting. Only one last effort was needed to crown our victory, to reach the summit of the most dangerous 8000-meter mountain along a new route. I have stubbornly aimed not to take the easier way. One’s plans can only go as far as the circumstances allow. After a thorough rest and a long talk with Simone we decided not to climb the buttress but attempt to follow the footsteps of the first group. Tomorrow we would leave all now useless equipment and follow the easier route. Simone felt better in the morning. At high altitude, illness generally develop swiftly, and a cold can develop overnight into a serious inflammation of lungs (pulmonary edema???). Happy that my partner is healthy again, we climbed to 7200m with light packs where we met with the four summiteers. They moved on down into the maze of the icefield while we set up tent and prepared for the final push. In general, the “French” route on Annapurna follows mainly ice and snow. The icefalls that fall along the north face of the mountain to 4300m are very dangerous. We hear the thundering of collapsing seracs in the middle of the night. The upper part of the mountain always accumulates a large amount of cornices making avalanches a serious problem. Within a few hours of a snowfall at camp 2 we counted more than 30 of the “white deaths” flying down. This is why the first ascent route did not become a “classic”, unlike on Everest or Cho-Oyu where large numbers of alpinists continue taking the first ascent route to the summit. On Annapurna, majority of the expeditions prefer to take a more complicate route to the summit – Bonington, Japanese, Polish, etc. For us, acclimatized this year at other high peaks, our safety on this mountain depended on the speed of our progress. We were to avoid moving slowly through the fields of seracs and cross icefalls first thing in the morning. The camps on our route are traditionally placed at 5000, 5900, 6800 and 7200 meters. The areas are spaced out to match the normal pace of the climbers and in relatively safe spots. The view of the upper mountain imprints into every climber’s memory. A glacier of a characteristic form (nicknamed “serp”) crawls down from under the summit. Its crevassed lower part gradually rises to the upper summit tower, about 200m high. Our fourth camp lies at the “handle” of the “serp”. We

spent the whole day drinking tea and resting before the decisive

push. Simone got gradually better and more optimistic. We spent

a few hours worrying at night after being informed on the radio

that Korshunov got lost somewhere in the icefall. He was found soon

after Simone and I put on our crampons to go searching for him. What a situation! Simone said that I should continue alone if I like while he goes back down. But alone? I understood at once there will be no second chance. Either now up for the summit, or back home. After thinking for a while I untied from the rope, which slid down the ice slope towards Simone’s headlamp. I shouted I’m heading for the summit, turned around, and climbed up the ice slope towards the rocks. The moon was out. The eerie greatness of the night covered everything a man lost if the world of altitude can sense. I was alone. Alone as no one else in the world. Just the stars, the ice, the rocks and the snow, and one lieutenant of CSKA Kazakhstan filled with determination. All or nothing – the motto pushed me along the flat fields of ice and snow right into the space. I sped up after Simone turned around and my feet stopped freezing. I walked up 20-30 steps and then took a breathing break. First up along the rocks, then a traverse to the right. Here I encountered the tracks of the Germans and followed them to the summit pyramid. It got very dark underneath it, for the moon was now on the other side of the mountain. I had to climb up a steep and narrow rock couloir covered with snow in places, as if inside a well. And then, after a few hundred meters, at 1:20am on May 30, I stood on top of Annapurna. The

uppermost point of the mountain is narrow as a blade made of firn

snow. The south face dropped on the other side like the entry to

the underworld. The darkness at the base of the mountain was awesome,

like water in a bottomless pool. The moon has just set at the horizon,

and from it through a barely perceptible cloud of mist a lane of

light came my way. The silver tower of Daulaghiri hung in the sky

between the stars. After warming the video camera underneath my

armpit I took some shots from the summit… The expedition was over. Evaluating it we can say that the new route on Kali-Himal climbed in the Himalayas is undoubtedly a great achievement for Kazakhstan alpinism bringing about optimistic thoughts for the future. Taking into account the fact that our sportsmen did not put a new route in the Himalayas since Daulaghiri 1991, I hope that the the work in the steep walls of Himalayan giants will start again. Sport ascents can not be reduced to climbing the mountains along their first ascent routes and routes done decades ago. For me, this experience was very valuable and allows me to make the following conclusions. The complexity of climbing in a small group, especially with the representatives of the “western” school of mountaineering, allows for a relatively free choice of objects for serious mountaineering and climbing tasks. Undoubtedly, the prestige of Kazakhstan sport can only gain from this. Of

course, the sport side of our expedition lost somewhat from the

fact that we did not climb a new route on Annapurna. This was caused

by the indisposition of my friend which, unfortunately, is in part

determined simply by luck. Nevertheless, the ascent of the mountain

adds to the treasure box of the Kazakhstan mountaineering. Denis Urubko

|